(This post was originally published in April 2022, and has been occasionally updated where additional information has been released)

The Stroud to Bishop’s Cleeve Gloucestershire cycling route is the dominant feature of our county’s cycling strategy.

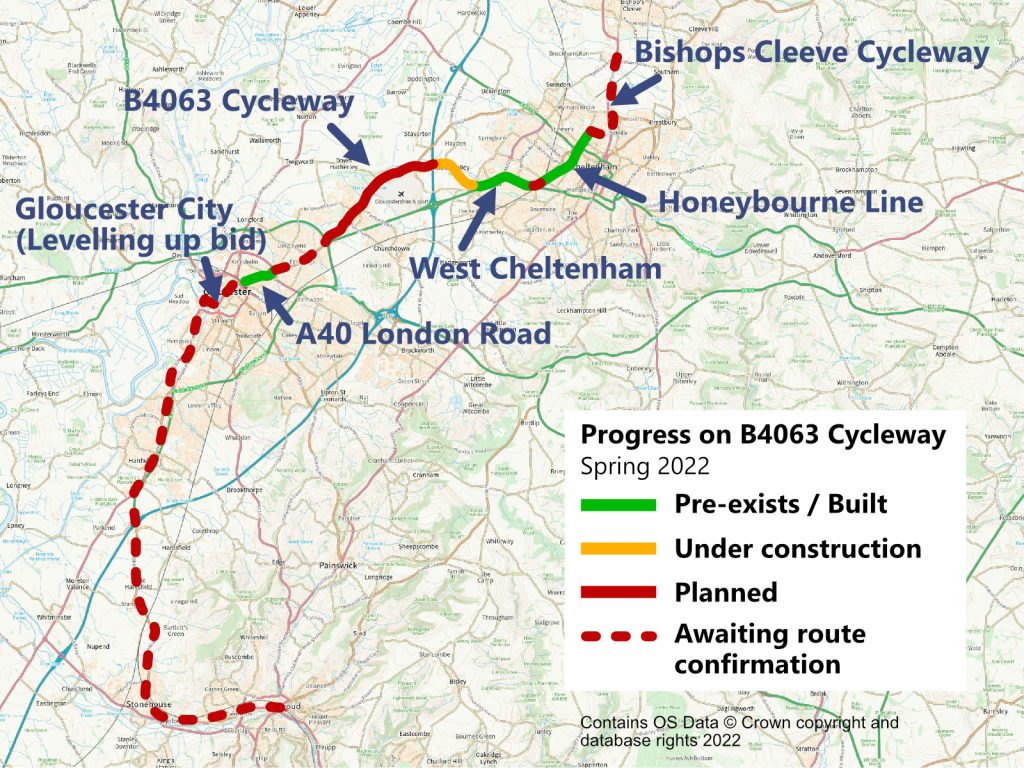

As the Cheltenham & Tewkesbury Cycling Campaign, we remain critical of Gloucestershire County Council’s prioritisation of this singular, marathon length cycle-spine route from Tewkesbury to Stroud as the means to deliver the necessary increases in cycling for the county, particularly given the delivery of initial sections of the B4063 and A40 route from Cheltenham to Gloucester.

With the route’s promoted as the heart of the Greener Gloucestershire campaign, we’ve brought together our top seven reasons why we think the approach will deliver lower value for money in helping people cycle compared to more targeted local schemes, and why we think broader action is needed to achieve the ambitions of our county.

“Why would a cycling campaign disagree with a Gloucestershire cycle route?”

Whether you are a county councillor wondering why we’d challenge your plan, or a local resident not sure whether your council tax is being invested wisely, here’s why we think this marathon cycle route is the wrong priority for a Greener Gloucestershire at this time.

7 reasons we believe Gloucestershire’s 26-mile cycle spine route is the wrong priority

1. It has massive opportunity costs

The cycle journeys that are easiest to enable through investment are the short ones, usually under 3 miles. Very few people want or are ever likely to cycle a 26-mile marathon.

However, the many opportunities and actions that enable these shorter trips are still stuck on the shelf because the priority of building the ‘longest continuous route’ soaks up the vast majority of funding, bids and council time year on year across Gloucestershire.

You may have seen Gloucestershire County Council’s budget video promise in early 2022, that it ‘delivers 26 miles of cycle track’;

As was obvious at the time, it didn’t actually build all the route, particularly south of Gloucester.

Despite several million pounds of council tax money already committed, it’s not even halfway to completion. Funds are not yet identified for several sections, and the total cost could easily exceed £30 million.

The 2022 route announcement looked very similar to the 2019 route announcement, and it appears the same news will be revisited several more times before other priorities are considered.

Spending several years building one cycle spine route distracts from and delays the many local measures urgently needed across the county.

Building one marathon length cycle route over several years is not going fast enough, particularly when it becomes the excuse for delaying action elsewhere.

We have always agreed some sections are needed, particularly the Cheltenham to Bishop’s Cleeve cycle route. However, focussing on getting to having ‘the longest’ means other, higher-priority interventions across Gloucestershire’s communities remain delayed and unfunded.

[Update May 2022 – The Bishop’s Cleeve cycle route, which has been on our wish list for many years, appears to have finally been successful in being prioritised for national cycling funding. We are awaiting final confirmation of what the grant will deliver.]

There is insufficient focus and investment in local enabling and supporting measures because the strategy assumes the 26-mile cycle spine will be transformative in near isolation, and that several more years can pass before other steps are taken.

2. It is being built the wrong way round

Gloucestershire County Council has chosen to build the rural B4063 sections first, despite the greatest potential for encouraging cycling being in the urban areas, where risk and demand are highest.

For example, an existing shared path from Churchdown to Elmcourt Roundabout will be upgraded in the early part of the scheme…

…whilst, the hostile section in Gloucester from Longlevens through to crossing the Estcourt Roundabout, a major barrier for accessing Gloucester City Centre, was left until a later phase, where the challenges of this section become clear.

Further in, the London Road section which consumed the vast majority of COVID active travel investment for the county stops just short of the most difficult section approaching the rail bridge. No designs have been proposed for this section by Spring 2023, over a year after construction of the less popular rural section started.

Similarly, the long promised and much needed Bishop’s Cleeve to Cheltenham cycle route was placed down the list for funding, with early money in this area being spent on increasing road capacity.

The only justifications we see for building rural sections first are;

- a desire to show a high number of miles built, irrespective of where they are, and

- to defer making the braver but essential leadership decisions about road space allocation and restriction of private motor traffic that tackling the urban areas (where most people want to cycle) requires.

3. It is competing against huge road schemes

The vast majority of Gloucestershire County Council’s highways expenditure continues to go on creating bigger roads.

Our 2022 investigation of the Gloucester South West Bypass raised concerns that cycle routes can easily be used to greenwash large road expansion schemes.

On the Bishop’s Cleeve cycle route, the majority of early spending has gone on increasing private motor vehicle capacity at the A435 Southam Lane junction.

The M5 Junction 10 scheme will be next in the queue for this, closely followed by an additional M5 junction for Tewkesbury near Junction 9, including an additional potential link road parallel to the M5 motorway route.

Major road schemes induce traffic. By making it easier to drive, more people will do so, often at higher speeds as roads are widened and straightened.

These extra motor vehicle trips start and end in local streets, which gain no benefit from a single, long cycle route, making it even harder for people to cycle in their local community.

The increasingly poor experience of local streets full of cars, combined with fast, dangerous feeder roads, means that some people will never feel confident even to get to this one strategic cycle route.

A single 26-mile cycle spine route pales into insignificance against the number and scale of road schemes that continue unabated across the county.

We believe every recent major road scheme in Gloucestershire has led to less cycling despite the token, but invariably inappropriate, cycle facilities included in them.

4. There is minimal planning of connectivity to the cycle route

One of cycling’s best features is its flexibility, being truly door to door.

When the right conditions exist, it addresses issues of inequality (of gender, income, ethnicity and more), and is particularly useful for those who need to trip-chain between caring, work and home responsibilities.

But accessibility must reach to people’s front doors.

Other than one small mini-Holland bid (still in development in early 2023) in north Cheltenham, there is little priority being given to addressing local road conditions to let people get to this route.

For example, the majority of people in Churchdown will need to use one of two uncalmed feeder roads to access the B4063 cycle route, each with high motor vehicle volumes.

Delays in the rollout of 20mph limits, gaps in road harm reduction plans, rejection of widespread school streets, and no strategy to prevent through motor traffic spoiling residential areas means that the vast majority of local people will see the cross-county route, but will never dare ride their local streets to get to it.

“The vast majority of local residents will see the spine route, but never dare ride their local streets to get to it.”

5. It is designed with a leisure, and not a daily travel, mindset

The claim that this route will be a useful connection from Stroud to Cheltenham or Tewkesbury for transport is weak.

A lazily winding S-shape route reflects a planning mindset that cycling is about leisure rather than daily utility transport, and that cyclists can be sent out of the way rather than inconveniencing motor traffic.

Whilst e-bikes are extending ranges for those able to invest in and secure them, the full length of this route will be of little value except to the fittest or least time-pressed of cycle users. Furthermore, there are already shorter, safer and potentially more pleasant route options for cycling between most of the towns.

If the council wants people to get out of their cars, it needs to offer local, direct and convenient routes focussed on shorter trips. This needs integrated local planning, not a single long-distance spine route.

6. It has weak, slow and dangerous sections

Separated cycle routes can benefit some cycle users, but this requires plenty of space and consistently high standards. Most of the Cheltenham to Gloucester route is in a space-constrained corridor and scrapes through on compromised or borderline compliance with standards.

When trying to encourage reluctant or new cycle users, cycle routes are only as good as their weakest sections. As we’ve highlighted in our consultation responses to date, attempting to squeeze the route through narrow sections rather than finding alternative solutions, means some sections will increase danger and be unpleasant for both pedestrians and cycle users.

Generally throughout the route westbound cycle users will ride much closer to oncoming traffic than is ever the case on the road.

Narrow footways also provide a poor environment for those on foot, especially when they are required to squeeze single file between a fast and noisy road and the cycleway. Many, quite reasonably, choose to walk side-by-side away from the road in the cycleway, engineering in conflict between active travel users, rather than addressing the problem of motor traffic.

Bad rearward visibility at junctions and driveways will prevent cycle users from protecting their safety without stopping, and it is difficult to maintain momentum at crossings, a key requirement of a utility cycle route.

Similarly, long delays at signalised crossings without approach sensors will add frustration.

People who therefore continue to cycle on the road will, however, face increased aggression from drivers who no longer think they should be there. Overall this route is likely to worsen safety rather than improve it for many cycle users.

It is well below the aspirations of the LTN 1/20 standard, and will be a noisy and unsafe ride experience.

Although segregated cycle routes can lead to more cycling, they need to be exemplary throughout to incentivise the significant change in transport behaviours claimed for the cycle spine. This is not, and will not.

7. It will weaken the case for future change

Media outlets regularly run the ‘motorists stuck whilst cycle lane empty’ headline, and we already hear some Gloucestershire county councillors say that money should be prioritised for cars because ‘no one uses the cycle lane near me’.

When challenged on what Gloucestershire is doing for cycling, the standard response is that ‘the council is building a 26-mile cycle route connecting Stroud to Bishop’s Cleeve and Tewkesbury’. However, a single strategic route does not mean the council is ambitious for cycling.

“A single strategic route does not mean the council is ambitious for cycling”

As described above, hostile environments away from the route mean uptake will be limited, particularly as ongoing road expansion increases motor traffic volumes and speeds.

It risks being a white elephant across the middle of the county.

It’s also unclear if many existing cycle users will use it. Particularly where the route is interrupted by long delays at signals for dedicated cycle crossing phases, or poorly built side junctions where a cycle user has to slow down because traffic may not stop, or where a narrow path forces a cyclist closer to a lorry than would ever be legal on the main carriageway, it’s easy to understand why cycle users will choose to stay faster and safer on the road. This frustrates other road users, and can further increase road aggression to cycle users.

With all the challenges we’ve highlighted above, it’s likely that sections of this route will be quiet for years to come. These will be cited as reasons that cycling ‘won’t work in Gloucestershire’, whilst road congestion rises further.

This will undermine the ability to prioritise and bid for the local links and street level actions that most people are waiting for to swap their shorter journeys to cycling, as the county continues a strategy of trying to build even bigger roads and more anti-cycling roundabouts to ‘fix’ congestion.

So what should a Gloucestershire cycling strategy look like?

The Cheltenham & Tewkesbury Cycling Campaign is the largest cycle campaign organisation in Gloucestershire and one of the oldest in the UK. It is a mix of experts by profession and experience, including a wide breadth of local residents of all ages.

We hold a clear vision that:

“Everyone should feel able to cycle from their front door to wherever they want to go.”

We believe a huge increase in cycling is vital for a Greener Gloucestershire.

We think that the first priority should be cycling within the urban cores, where the most rapid and effective change can be achieved.

Why prioritise intra-urban cycling first?

- Cycling is fastest and most accessible for journeys of up to around 3 miles. Most of these journeys occur within our towns.

- Cycling in this context can be done by almost anyone with the right conditions.

- Cycling is equitable and cheap; a basic bicycle can be obtained easily and is accessible to those who have no access to a car, and parked for free at the destination, without ongoing fuel costs.

- Cars are hungry for space in our towns and city. More lanes create more traffic, and parking blights almost every street in our residential and commercial areas.

- Cars do maximum damage, in terms of air quality, noise and road violence within our urban areas.

- Building and maintaining ever larger spaces for private cars is hugely expensive, inequitable and incompatible with policies to address climate change.

- Increasing traffic is one of the biggest planning barriers to the urban housing we need.

- Cycling is truly door to door.

Given all of the above, the focus of any cycling policy that wants to change behaviours and maximise benefits must address journeys under three miles first.

Only after local trips begin to switch and local streets are calmed do longer distance routes become relevant.

Solutions need to be built out from the creation of liveable towns with better social cohesion, where the private car does not dominate and where traffic is reduced for the benefit of those who do need to use a private motor vehicle.

This cannot be achieved by a single, marathon length cycling route, delivered over several years, whilst local areas are left at the mercy of rising traffic levels, sprawling roads and more high-speed roundabouts.

It needs early, integrated investment to remove barriers, set default lower speeds, open up short cuts, increase permeability for active travellers, and reallocate space away from private cars. Any strategic network investment must be of impeccable quality, comprehensive and initially focussed where most trip potential can be achieved, accessing each of the urban cores.

For us in Cheltenham and Tewkesbury, it’s obvious really…

It needs to be easier to cycle to school before it’s easier to cycle to Stroud.

Whilst some sections of the route could help if done well (such as Bishop’s Cleeve to Cheltenham), spending large sums of council tax and staff time on a single piece of infrastructure whose potential for increasing cycle use is limited at best cannot enable lots of short journeys for everyone, every day.

This means that too many Gloucestershire residents will wait even longer before they feel safe to cycle from their front door.

So what next for the cycling campaign?

We have committed to continue our scrutinise of the scheme elements as they come forward.

Given the council is pressing ahead, it’s vital the Gloucestershire cycle spine at least delivers on quality and safety, even if it doesn’t deliver on value. As a cycling campaign, we will do our best to work with GCC to ensure this.

Indeed, the sections of the route through Longlevens and Gloucester look to be where there is greatest risk of compromise on quality and safety unless the council is really willing to challenge private car dominance.

We’ll also continue watching closely to challenge what we see as ‘greenwash spin’ and inappropriate use of active travel funding.

Our ‘wish list‘ remains important, highlighting the local interventions that could have the biggest impact.

Our county has so much unrealised potential for cycling.

Gloucester has poor public transport and huge inequality that cycling can easily address., Whilst in Cheltenham cycling levels have held up despite more and more motor traffic, it is far from the exemplar cycling town of England that it could be. Towns such as Tewkesbury, Stroud and Cirencester with their strong sense of place could also realise incredible transformation if car dominance is addressed.

That change won’t be unleashed by a single ‘Gloucestershire Cycle Spine’.

It needs leadership of an integrated and locally prioritised strategy, urgently starting now, if we are together to address the congestion, climate, energy and community emergencies we’re all facing.

This is the vision we’re seeking to champion.

Why not join us?

If you’d like to see a greener and fairer Gloucestershire, and think cycling is an important part of achieving this, why not add your voice and join us today?